Imagine being on a planet around a star on the far ends of the warp. Great view of the rest of the galaxy!

TL;DR

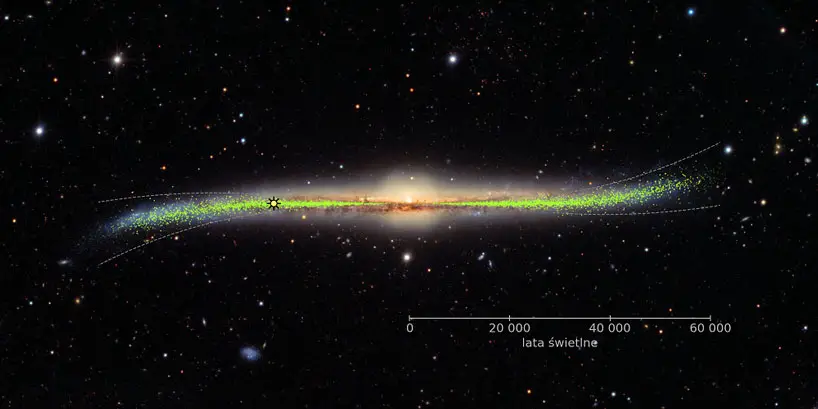

Scientists have created a detailed 3D map of the Milky Way, revealing that our galaxy is warped into an S-shape. By analyzing over 2,400 Cepheid stars, researchers found that the galaxy bends and twists like a beach towel, with outer stars situated 5,000 light-years above or below the central plane. This warp begins about 25,000 light-years from the galactic center and becomes most pronounced at 60,000 light-years. These findings provide new insights into the history and structure of the Milky Way, potentially caused by past collisions with smaller galaxies or gravitational forces.

Our galaxy is far from flat—it’s actually quite warped.

This is what the latest three-dimensional map of the Milky Way suggests. By accurately determining the locations of over 2,400 pulsing stars, some from the galaxy’s outer regions, scientists have created one of the most detailed maps of the Milky Way ever seen.

Their findings, published in Science, reveal that our home galaxy isn’t the flat disk often depicted. Instead, it’s twisted into a wave-like form, similar to a beach towel being shaken out.

This isn’t the first time researchers have noted the Milky Way’s warped shape. However, studying this warp in detail could provide insights into its history and help us better understand our position in the cosmos.

“This is significant and exciting research,” says Kathryn Johnston, a Columbia University astronomer who wasn’t part of the study. “Creating a three-dimensional map is incredibly challenging, so it’s fantastic that [the researchers] were able to produce a global map that spans the entire galactic disk.”

For decades, astronomers have suspected the Milky Way might have a slight warp. Back in the 1950s, astronomers studying hydrogen gas in the galaxy noticed irregularities at its edges—a finding that was later supported by observations of cosmic dust and the movement of stars across the galaxy.

But conclusively proving the warp’s existence has been difficult. While astronomers can easily capture images of distant galaxies, our view from within the Milky Way isn’t as advantageous. Johnston likens it to trying to map a forest from its center.

While the idea of installing a telescope beyond our galaxy remains a distant dream, a team led by Dorota Skowron, an astronomer at the University of Warsaw, decided to tackle the problem by mapping the Milky Way using Cepheid stars—bright, young stars scattered throughout the galaxy.

Cepheids are especially useful for measuring cosmic distances. They can shine up to 100,000 times brighter than the Sun, making them easy to spot even from thousands of light-years away. Their brightness also varies in a predictable way, allowing astronomers to calculate their absolute brightness and then compare it to how bright they appear from Earth, giving a precise measure of their distance.

As part of the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE), Skowron’s team analyzed more than 1,500 Cepheids across the Milky Way, supplemented by data on 900 more Cepheids from other sources.

Together, these stars mapped a large portion of the galaxy, some within 13,000 light-years of Earth and others located over 100,000 light-years away at the galaxy’s edges.

With this data, the researchers created a comprehensive three-dimensional map of the Milky Way—the clearest depiction of our galaxy to date, according to Skowron. “This isn’t an artist’s rendering or a model. It’s an actual image of our galaxy,” she explained.

The resulting map revealed a familiar structure with a surprising twist: the Milky Way is bent into an S-shape, with peaks and valleys on either side. (Depending on perspective, our Solar System is either near the top of a wave or at the bottom of a trough.)

The warp begins around 25,000 light-years from the galactic center, reaching its maximum at around 60,000 light-years out. Some of the outermost stars are about 5,000 light-years above or below the plane of the galaxy. This produces an 8 percent slope, which Skowron says would be visible to the naked eye.

The model also showed that the galaxy’s edges are thicker than its center, giving the Milky Way a bowtie-like shape when viewed from the side. This happens because, as stars and gas become less dense farther from the center, gravity exerts less influence, allowing the galaxy to stretch out.

These findings support another study published in Nature Astronomy, which also used Cepheids to map the Milky Way. While both studies yielded similar results, the new research stands out due to its larger sample of Cepheids, says Heidi Jo Newberg, an astrophysicist at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Though not surprising, the findings are “a significant step forward,” notes Debra Elmegreen, an astronomer specializing in galaxy evolution at Vassar College. “What we’re seeing isn’t vastly different from what we’ve known, but it refines our understanding.”

To Earthlings, the warped shape of the Milky Way may seem strange, but it actually aligns with the structure of many other spiral galaxies—at least half of which are also warped. What causes these distortions remains uncertain, but some astronomers theorize that the inner stars of a spiral galaxy pull on its outer regions as they rotate. Others believe these deformations are the remnants of past collisions with smaller galaxies.

More research is required to determine if these theories apply to the Milky Way. In the meantime, Skowron notes, just knowing the warp exists is a major discovery.

That said, mapping the entire galaxy is still a work in progress. Dust clouds near the galactic center make it difficult to see stars on the far side of the disk, and many of the Cepheids in this study were located on the same side of the galaxy as our Solar System. As a result, some parts of the map are less detailed than others, Elmegreen says.

In these cases, data from other stars, gas, and dust might help fill in the gaps. While less precise than measurements from Cepheids, these alternative sources can still provide valuable information, says Newberg. Given the complexity of the Milky Way, all data sources are useful. After all, understanding a forest requires more than just counting its tallest trees.

“Every method of mapping the galaxy offers a different perspective,” Newberg says. “They’re all pieces of the puzzle.”

Although scientists have mapped many Cepheids, they represent only a tiny fraction of the stars in our galaxy. But that’s even more reason to keep exploring, says Elmegreen. “After all, the entire sky is still out there.”